CHAPTER 5 – ECONOMY, NATURAL CAPITAL

Why Include Natural Capital

Addressing this question, Herman Daly observed: “There is something fundamentally wrong with treating the earth as if it were a business in liquidation.”

5.1a Our Wrong Assumption.

From its inception, capitalism has assumed that resources would be inexhaustible and also that financial capital could replenish them—or more recently, that technology could replace them. Consequently, in the supply and demand equation, the price of a resource reflects a consumer’s willingness to pay rather than of any accounting of its physical exhaustion. This assumption that financial value is interchangeable with natural value is now causing serious environmental and social problems, for example:

- The price of a species of fish goes up with dwindling supply – but never enough to pay the price for its extinction.

- The practice of clearcutting lumber from public forests continues to meet public demand – without ever accounting for the cost of destroying the forest ecosystem’s services, of the loss of species biodiversity, or the nutrient loss due to erosion of the land, and wild fires.

- The price of the vital element phosphorus does not account for its limited supply or risk of permanent loss, on the impossible assumption that someone will invent an alternative to an element essential for life

- The price of oil is not determined by the cost of its geological diminishing returns, nor by the increasing costs of the environmental and social damage caused by its extraction, refining, and combustion.

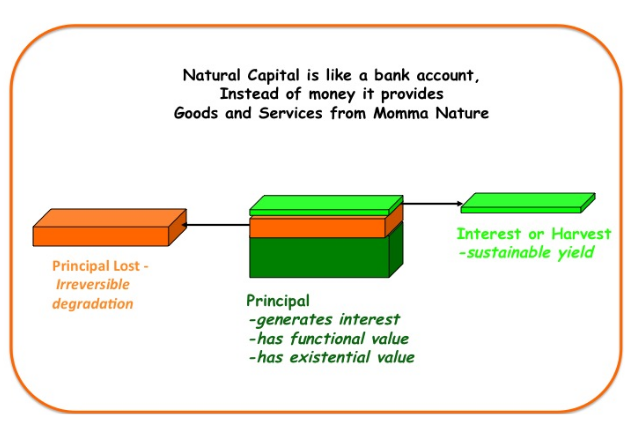

The concept of Natural Capital , the natural goods, and services derived from the environment, can usefully be described as analogous to a bank account (Fig. 1). That is, natural capital represents the ecological assets that we use freely and on which the economy depends, but that is omitted from economic assessments. For example, Costanza , et al.3 (2011)estimated the current value of the annual global ecosystems services and natural capital to be within a range of 16-54 trillion dollars, which was then more than comparable with the global GDP of 72.9 trillion. As in Fig.1 of Chap. 1 we are now utilizing 150% of the annual4 global ecosystems’ biochemical production and thereby spending down its global principal. This utilization derives from three categories of human activity: harvesting (e.g., overfishing), wasting (e.g., pollution), or modifying (e.g., occupying) . The combined effect of these activities, done in excess, is to weaken the hosting Earth Systems and lessen their function, production, and resilience to disturbances. By continuing to do this we are effectively reducing the annual production of renewable resources—that is, we are depleting the principal, thereby reducing its capacity to reproduce new Natural Capital.

5.1b. Are we misusing Renewables?

Humans use natural resources in several ways through harvesting, polluting, wasting, development, and enjoyment. The first three uses have mutually interactive values in favor of humans, but with a cost to nature, and the fourth is more mutual and contributes as an existential or aesthetic value. Ecosystems produce goods that are harvested for e.g. agriculture, fisheries, forestry, and lumber products. Ecosystems also preserve these services for humans by their intrinsic capacity to self–renew through their reproductivity, their biodiversity, and their resilience such that they maintain their capacity to grow and maintain these goods and services. But when humans destroy ecosystems physically, over harvest them, or contaminate them, they also destroy the very services that humans enjoy. We develop land for urban and industrial purposes, and we pollute the soil. We use and pollute freshwater sources. We destroy the marine trophic chain from the top down through overfishing the stocks of fish and large marine animals; and we destroy the trophic chain from the bottom up by reducing the photosynthetic marine production phytoplankton, which generate a huge percentage of atmospheric oxygen) through the effects of land-pollutant runoff, eutrophication, and ocean acidification all caused by excess carbon dioxide. By polluting the atmosphere, we are changing the climate’s carbon cycle, reducing oxygen concentrations in the atmosphere and oceans, physically destroying marine coastal and coral-reef habitats, changing ocean current circulations, and raising global sea level.

Read More