CHAPTER 2 – COMMUNICATION

1. CAN WE IMPROVE CREDIBILITY?

1.a. Expansion of Communication.

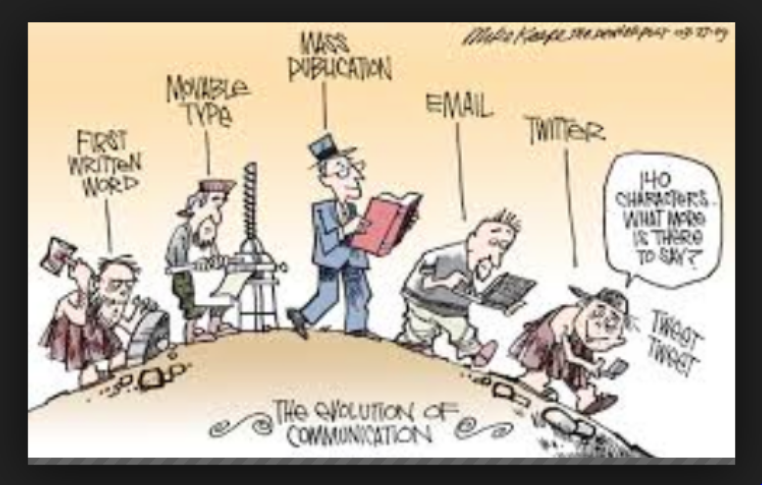

What humans communicate has remained relatively constant compared with how we communicate. For most of human existence since the development of language, communication was face to face. Methods for memorization (including all the kinds of sound patterning like rhythm, alliteration, and rhyme that mostly now belong to poetry and advertising slogans) facilitated the inter-group and intergenerational transmission of information in these oral societies. Then, between 5,000 and 3,000 years ago, writing was developed in several different cultures from simple pictographs and symbols into the actual representation of language.

Writing is a technology so powerful that literacy significantly alters the human brain. It also made possible the explosive growth of vocabulary and the development of more complex abstract thinking. The invention of printing with movable characters, first in China around 1040 CE, then in Europe in the fifteenth century, was a revolution almost as powerful, because it allowed knowledge and ideas not only to be preserved but spread far more widely and rapidly. By the late 1500s in Europe it was facilitating the growth of mass literacy, which blossomed across Europe in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The telegraph, the telephone, radio, film, and then television followed in rapid succession. Then, late in the twentieth century, the invention of the transistor microchip brought about the third great communications revolution: the internet and the mobile phone, which made possible not only email but the Web, texting, and social media (Fig. 1). Paralleling and facilitating these innovations, starting with physics, moving to chemistry and then, with the development of evolutionary theory and genetics, biology, was an equally rapid explosion of scientific and technical knowledge. Already by the mid-seventeenth century, it was impossible for one person to know all of European philosophy, mathematics, and science—let alone their equivalents in non-European cultures.

All this meant that the evolution of communications technology brought about an expansion of communicative content away from the concrete, sensory, and directly relevant within a single culture in the direction of material more abstract, more geographically distant, and less directly experienced— though photography, film, and television provided additional visual information. At the same time, since the development of print and via newspapers, magazines, broadcasting, and now the Web, the technological options for expressing opinions have proliferated, and because of a much wider range of media for transmitting information, any information that enters these media suffers a greater risk of distortion. The other reason for this is that science and technology are now so vast, diverse, multi-specialized, and complex that even a scientist in one branch of one discipline has to rely on the opinions of colleagues in other disciplines at some remove from his or her own; and the nonscientist public, the great majority, has to rely on the consensus within any scientific discipline on any topic of importance. The alternative, made possible by generalized scientific illiteracy created and maintained by weaknesses in the educational system, the cultural and political power of conservative religious institutions, and the profit-drive of commercial mass media, is to reject science in favor of dogma or pseudoscience—or both. As we will see, this dependence has profound consequences in an age when the power of technology is so great that its implementation has life-and-death consequences not just for society but for the future of the human species and a livable biosphere.

The core of the problem is an inheritance of tens of thousands of years of human biological and social evolution on how to judge the truth of a message, which commonly is that a listener first judges the messenger and then the message content. If the messenger is familiar personally, or appears to be from the same social milieu or otherwise “relatable,” the listener will tend to trust the messenger and then consider the content. If the content appears credible within the scope of the listener’s belief system or knowledge base, then the message is successfully communicated. For people without the relevant intellectual training—the immense majority in our society—failure to meet these two conditions also poses the risk of poor or null communication. Moreover, if the original information is repeated multiple times, the original information content can become distorted. Even the case of written messages that can be communicated without degradation, the same two criteria are valid: the credibility of the messenger and the compatibility with the receiver’s belief system or knowledge base.

1.b. Establishing Veracity and Trust as Journalist Goals.

Building trust in the content of a message involves a mix of two approaches: factual (showing that the facts have been verified) and opinion (showing that the interpretation is based on an authoritative source or sources). Scientific journals achieve a generally high level of truthfulness in two ways. First, they employ a peer-review process that checks for errors in the procedure, the data, or its interpretation. Also, they require for any published paper the repeatability of results derived from experimentation, observations, or accepted mathematical analyses. Journal reporting on medical and social research has similar criteria, but allows for a wider range of permissible error due to the subjectivity in human behavior and in the mode of observation. In both cases, the degree of complexity generates a corresponding uncertainty in the reported results. Consequently, the ‘truth’ is often expressed as a probability, such as a 40% chance of snow. Such pronouncements come with the warning that the uncertainty might be lessened as technology advances or with the widening of the relevant knowledge-bank of the studied system.

Read More