CHAPTER 1 – DEFINITIVE CHALLENGES

1. Human Predicament

1.1a Resource Debt

The planet’s human societies and its ecosystems are experiencing strong destabilizing trends to which national governments are not adequately responding. The root causes of these trends are global overpopulation and overconsumption.

Overpopulation is increasing the demand for consumption, and overconsumption is reducing the supply of renewable natural resources to a point of critically destabilizing global human society.

The industrial revolution of the eighteenth century resulted from colonial access to the resources of the New World which led to labor‑saving machines that used cheap fossil energy. The resulting huge increases in productivity spurred the development of modern societies and a culture without resource limits.

Today, we are still simultaneously ignoring and paying the impossible cost of this fallacious approach. The Human Predicament derives from the inability of humans to manage a quick and effective response to the multiple impacts that are now destroying the human habitat.

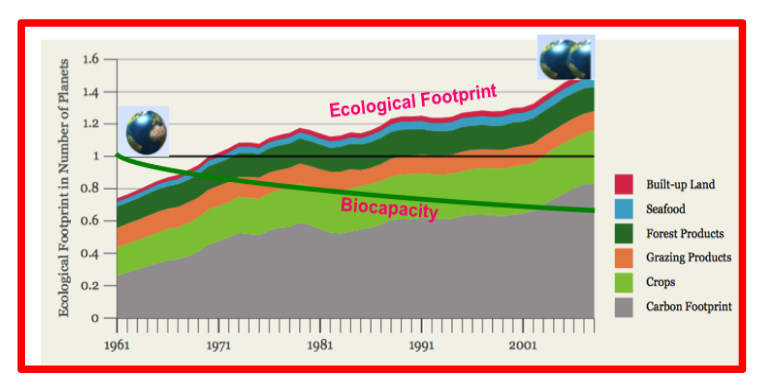

A recent accounting of the earth’s biocapacity (supply of goods and services from nature) and the human ecological footprint (demand for this biocapacity) indicates that we are consuming much more than what nature can replenish every year and are continuing to devour the remainder.

To put it another way, we are far past our carrying capacity (and have been more and more so since the 1970s), and are currently consuming more than 150% of the renewable resources that earth’s annual production can supply (Fig. 1). It is the divergence between these two trends of demand and supply that calls for an urgent transition to sustainability.

The reasons for this overshoot are economic, governmental, and cultural. In short, our technical capacity combined with our for‑profit economy have, together, outstripped our social responsibility and our ability to wisely manage our societies and our environment. This puts the entire human society in a very precarious, unstable, and unsustainable condition.

The transition to a more stable and sustainable world is still technically possible on the condition that we can obtain a critical level of public awareness, a restructuring of the global economy, a complete political commitment to Sustainable Development in accord with the United Nations, and a thorough collective international effort toward cooperative agreements.

The expression Global Change (GC) represents the degradation caused by exceeding sustainable limits of both the natural and human systems by all nations. To grow their financial wealth, over‑consuming societies tend to shield themselves from these problems, and they continue to pursue increased material wealth while ignoring their dependence on the rest of the world and neglecting their need for sustainable solutions. On the other hand, the overpopulated societies, severely affected by economic inequality, continue to gamble on large families to consume resources for their survival, and consequently, become less and less able to initiate sustainable solutions. Thus, overpopulation and overconsumption are the root causes of all the GC impacts, which, together with ignorance and lack of will to cooperate in solutions, create the Human Predicament.

The graph is normalized to values estimated to exist in 1961 — symbolized by the globe to the left — and extend to those in 2012, symbolized by the globe and a half to the right. In other words, by 2012, humanity was consuming 150% of the earth’s production relative to 1961.

The color code on the right legend indicates the contributions of the various human activities listed. The carbon footprint portion (gray and 55% of the total) is a measure of the human disruption of the Carbon Cycle that is changing the climate and impacting the ocean and land resources.

Graph from Footprint network. The biocapacity plot was calculated from data from the same source.”

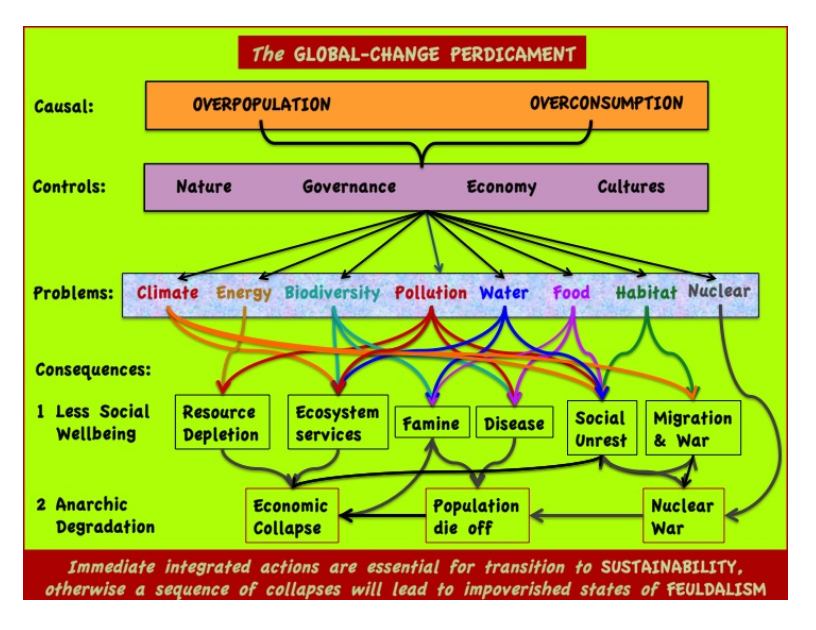

It is through a lack of systemic self‑regulation that these root causes have grown and have generated an aggregate of global mega‑problems that are reducing our resilience and precluding a return to stability (Fig.2).

The cumulative result of this situation is an exponential deterioration and destabilization of the natural systems that are threatening the continued support for the well‑being and perpetuation of all human societies.

While we try to mitigate prominent impacts separately, we overlook the preventive measures needed to reduce the two root causes, that is, by changing the controls that can regulate them (Fig.2). These impacts are so strongly interconnected that any combination of several of them could collapse modern society, whether through economic collapse, population die‑off, or nuclear war (Fig. 2).

Any of these collapse scenarios is clearly possible as an extension of the present global condition, and several of the worst are: financial instability, rampant malnutrition, infectious diseases, social unrest, failed states, border wars, mass migrations, and nuclear proliferation.

The main point of Fig. 1 is that time is a severely limiting factor — an urgency compounded by the continuing rate of depletion of per‑capita resource wealth, which makes our global society increasingly dysfunctional, and which depreciates our capacity to effect rational and just governance.

Collapse could mean a gradual loss of functionality and resilience, or it could mean abrupt phase shifts or huge natural disasters capable of triggering a cascade loss of functionality and resilience in all sectors of human society. But slow or fast, collapse is inevitable unless we immediately change course and accelerate sustainable development. We note the symbolic consensus of hope from the United Nations (UN) Summit 2015].

Global collapse avoidance requires an immediate change in how we manage the two root causes (Fig. 2) through a cooperative restructuring of management controls, especially the economy and government (cf. Chap. 3 and 4). The best approach to alleviating the degree of collapse is to initiate constructive corrections to these management controls and orient them toward resilience‑building for nature and sustainable development for societies (cf. Chaps. 4 & 5).

In addition to this approach is the need to help human communities understand the importance of these two goals and the self‑organizational processes required for the transition to more sustainable societies. With these measures and others (Chap. 5), we certainly can soften the collapse and rebuild from it.

Currently, the socially destabilizing consequences of GC (Fig. 2) are robbing us of the time and money urgently needed to devote to their solutions to prevent the anarchic degradation of our civilization.

Without intelligent controlling, these two root causes permit a continued growth of the major problems that are now threatening the stability of human habitat. These problems act both directly and indirectly, through a complex set of mutual interactions that are degrading the stability and the level of well-being of human societies. With continued degradation of resources, human society is becoming more susceptible to a cascade collapse in the form of economic disintegration, population die-off, and/or war.”

1.2a Wealth Gap

Today, humanity finds itself globally separated into three types of nations, according to their access to resources and their accumulated wealth.

These types are as follows:

- The most developed countries (MDCs that have achieved an industrial transition but are presently ignoring resource limitations.

- The least developed countries (LDCs that have not made the industrial transition and suffer from a lack of per-capita resources, due to a natural lack of them and/or their exportation.

- The developing countries (DCs), which form an intermediate group of nations between MDCs and LDCs, that are mostly following the industrial trajectory of the MDCs and thereby, are rapidly increasing their resource consumption.

The MDCs have maintained growth economies based on the consumption of resident resources and those imported from other countries. The LDCs have been mostly left out of the benefits derived from the world’s resource pool and are left to scavenge for survival because they lack the social and political infrastructure either to exploit their own resources or to prevent richer nations from exploiting them.

Both DCs and LDCs aspire to achieve MDC ranking. In this regard, it is of utmost importance that their development does not follow the polluting and unsustainable trajectory taken by the MDCs, but that they instead optimize the process of leapfrogging to renewable energy sources and their infrastructure, efficient technologies, non-polluting industries, just wages, and social services.